[ This is a content summary only. Visit our website https://ift.tt/1b4YgHQ for full links, other content, and more! ]

by Mehwish Mehmood via Digital Information World

"Mr Branding" is a blog based on RSS for everything related to website branding and website design, it collects its posts from many sites in order to facilitate the updating to the latest technology.

To suggest any source, please contact me: Taha.baba@consultant.com

Does your company target other businesses? Wondering how to use Facebook ads to connect with prospects? In this article, you’ll find four ways to use Facebook ads to reach B2B customers. #1: Target Specific Job Titles and Companies With Facebook Ads More than likely, you already have a good idea whom your target audience is. [...]

The post 4 Ways to Improve Your B2B Facebook Ads appeared first on Social Media Examiner.

Remarkable One Page website packed with gorgeous illustrations and animations for Genesis, a vegan restaurant based in Shoreditch, London. As you scroll the website bursts to life with animated characters, plants and even some of the typography. A great reference on how to create an unforgettable first impression.

The following is a short extract from Tiffany's upcoming book, CSS Master, 2nd Edition, which will be available shortly.

Transforms allow us to create effects and interactions that are otherwise impossible. When combined with transitions and animations, we can create elements and interfaces that rotate, dance, and zoom. Three-dimensional transforms, in particular, make it possible to mimic physical objects. In this piece, we'll look at 2D transform functions (3D functions are covered here).

There are four primary two-dimensional transform functions: rotate, scale, skew, and translate. Six other functions let us transform an element in a single dimension: scaleX and scaleY; skewX and skewY; and translateX and translateY.

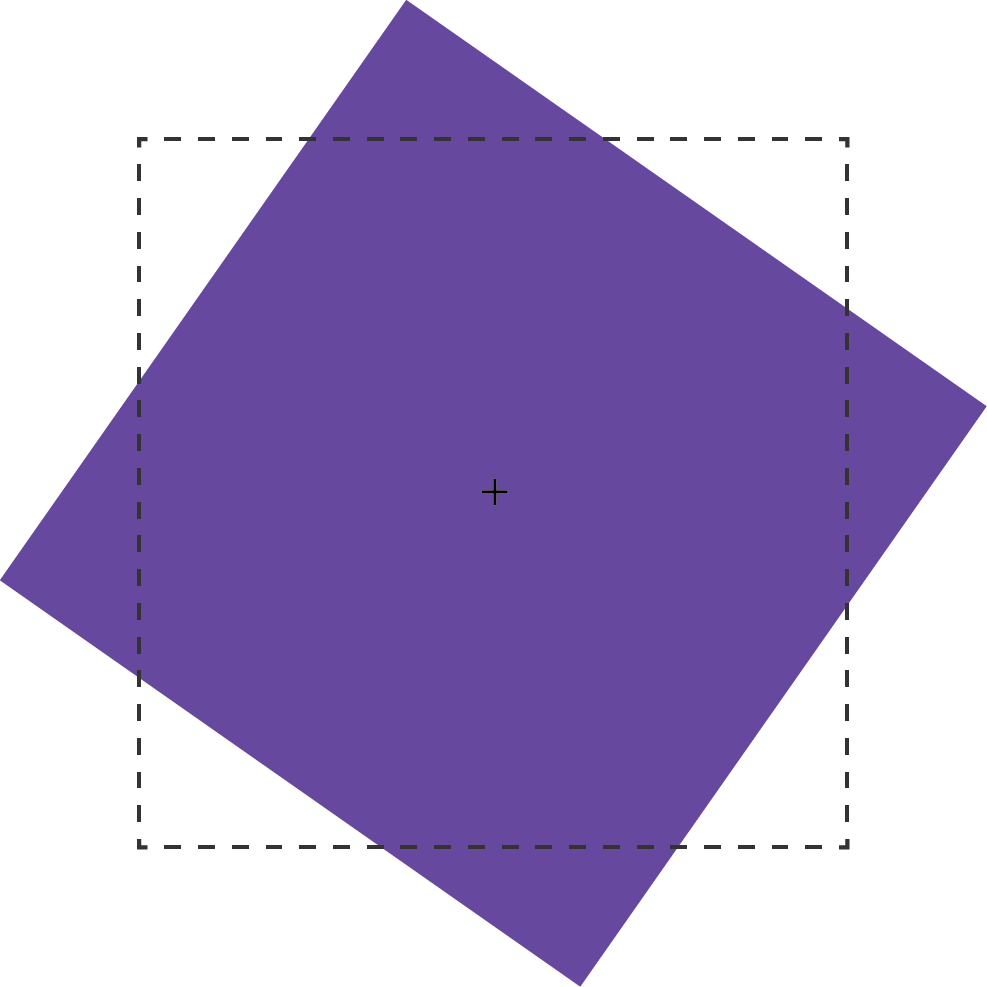

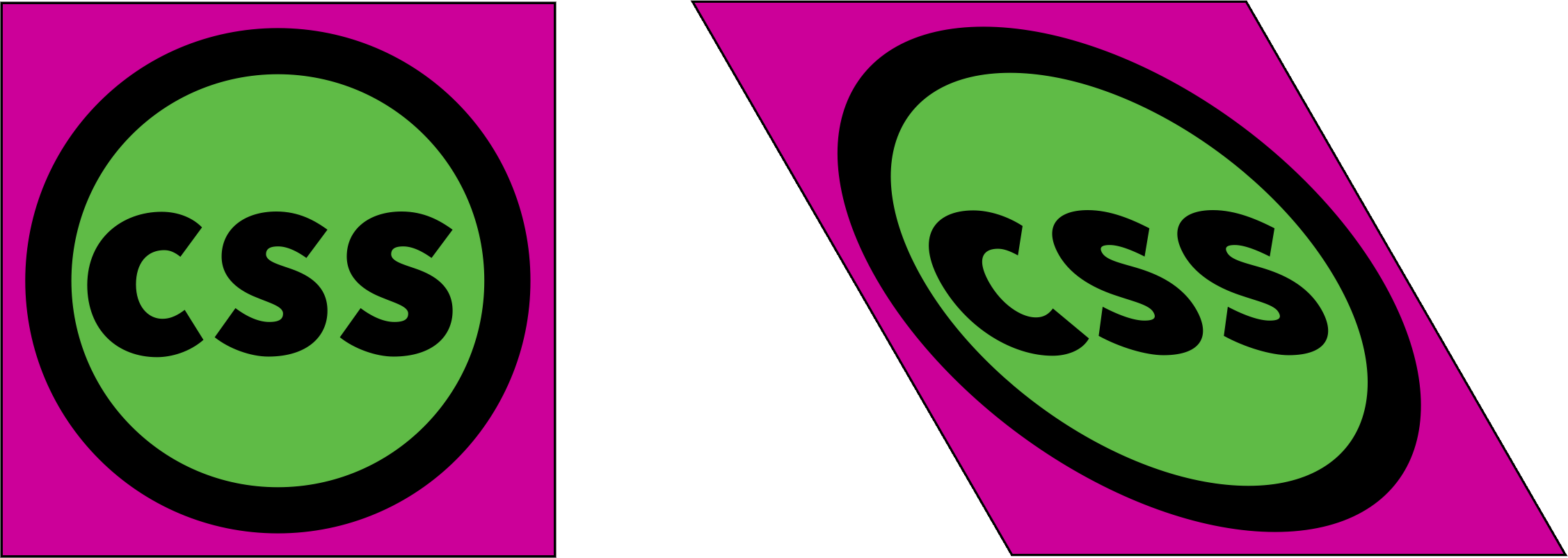

rotate()A rotation transform spins an element around its origin by the angle specified around the transform-origin point. Using rotate() tilts an element clockwise (positive angle values) or counter-clockwise (negative angle values). Its effect is much like a windmill or pinwheel, as seen below.

The rotate() function accepts values in angle units. Angle units are defined by the CSS Values and Units Module Level 3. These may be deg (degrees), rad (radians), grad (gradians), or turn units. One complete rotation is equal to 360deg, 6.28rad, 400grad, or 1turn.

Rotation values that exceed one rotation (say, 540deg or 1.5turn) are rendered according to their remaindered value, unless animated or transitioned. In other words, 540deg is rendered the same as 180deg (540 degrees minus 360 degrees) and 1.5turn is rendered the same as .5turn (1.5 - 1). But a transition or animation from 0deg to 540deg or 1turn to 1.5turn will rotate the element one-and-a-half times.

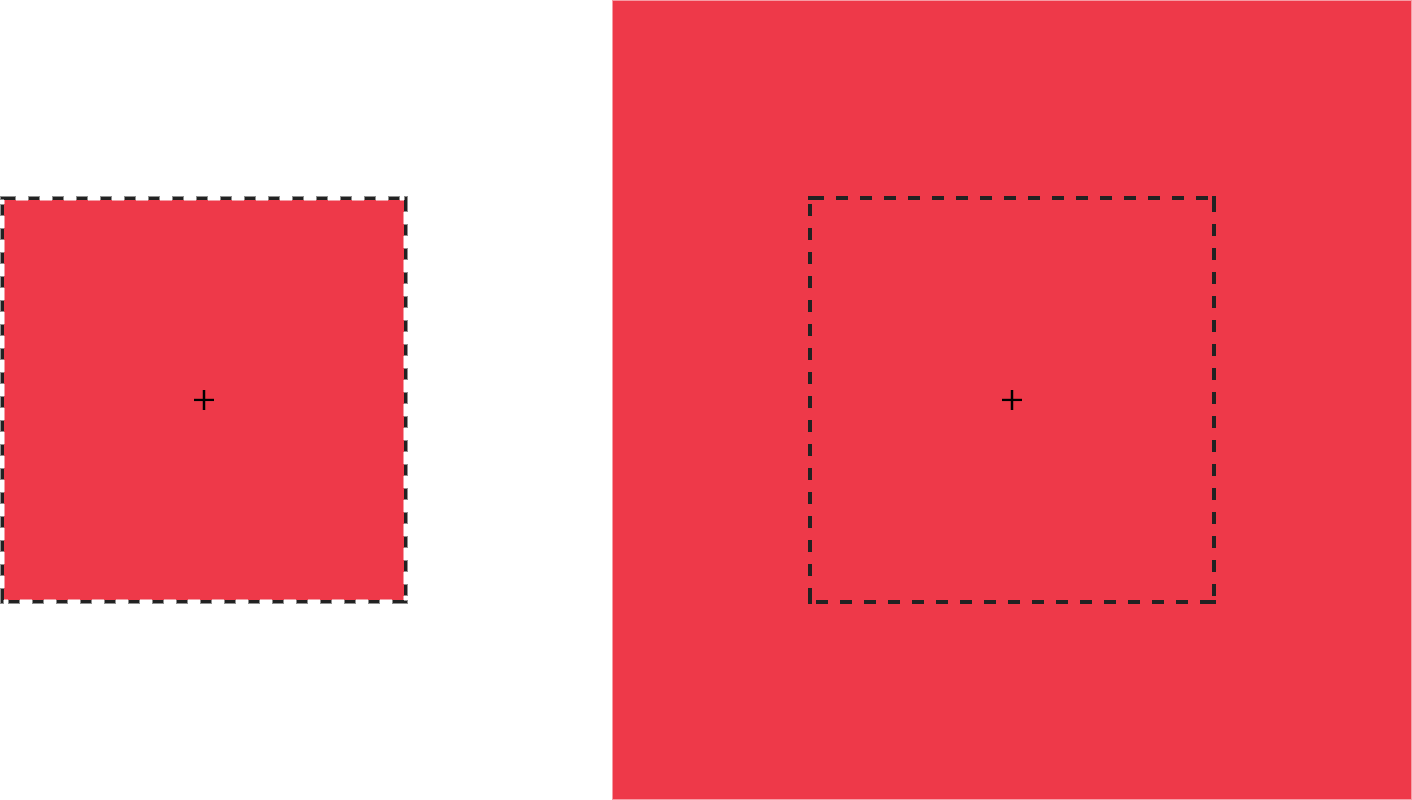

scale, scaleX, and scaleYWith scaling functions, we can increase or decrease the rendered size of an element in the X-dimension (scaleX), Y-dimension (scaleY), or both (scale). Scaling is illustrated below, where the border illustrates the original boundaries of the box, and the + marks its center point.

Each scale function accepts a multiplier or factor as its argument. This multiplier can be just about any positive or negative number. Percentage values aren’t supported. Positive multipliers greater than 1 increase the size of an element. For example, scale(1.5) increases the size of the element in the X and Y directions 1.5 times. Positive multipliers between 0 and 1 will reduce the size of an element.

Values less than 0 will also cause an element to scale up or down in size and create a reflection (flip) transform.

Warning: Using scale(0) will cause the element to disappear, because multiplying a number by zero results in a product of zero.

Using scale(1) creates an identity transformation, which means it’s drawn to the screen as if no scaling transformation was applied. Using scale(-1) won’t change the drawn size of an element, but the negative value will cause the element to be reflected. Even though the element doesn’t appear transformed, it still triggers a new stacking context and containing block.

It’s possible to scale the X and Y dimensions separately using the scale function. Just pass it two arguments: scale(1.5, 2). The first argument scales the X-dimension; the second scales the Y-dimension. We could, for example, reflect an object along the X-axis alone using scale(-1, 1). Passing a single argument scales both dimensions by the same factor.

translateX, translateY, and translateTranslating an element offsets its painted position from its layout position by the specified distance. As with other transforms, translating an element doesn’t change its offsetLeft or offsetTop positions. It does, however, affect where it’s visually positioned on screen.

Each 2D translation function—translateX, translateY, and translate—accepts lengths or percentages for arguments. Length units include pixels (px), em, rem, and viewport units (vw and vh).

The translateX function changes the horizontal rendering position of an element. If an element is positioned zero pixels from the left, transform: transitionX(50px) shifts its rendered position 50 pixels to the right of its start position. Similarly, translateY changes the vertical rendering position of an element. A transform of transform: transitionY(50px) offsets the element vertically by 50 pixels.

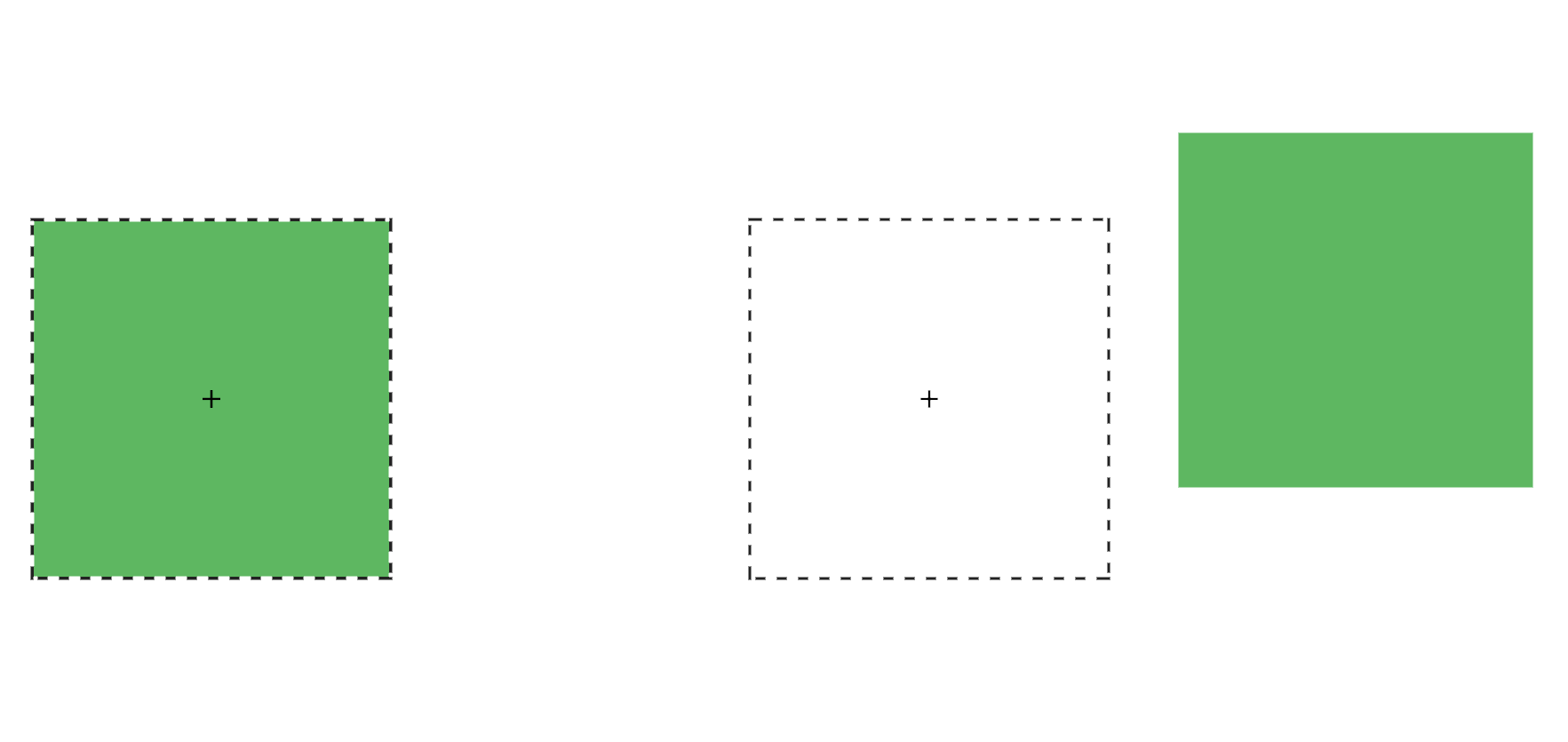

With translate(), we can shift an element vertically and horizontally using a single function. It accepts up to two arguments: the X translation value, and the Y translation value. The figure below shows the effect of an element with a transform value of translate(120%, -50px), where the left green square is in the original position, and the right green square is translated 120% horizontally and -50px vertically from its containing element (the dashed border).

Passing a single argument to translate is the equivalent of using translateX; the Y translation value will be set to 0. Using translate() is the more concise option. Applying translate(100px, 200px) is the equivalent of translateX(100px) translateY(200px).

Positive translation values move an element to the right (for translateX) or downward (for translateY). Negative values move an element to the left (translateX) or upward (translateY).

Translations are particularly great for moving items left, right, up, or down. Updating the value of the left, right, top, and bottom properties forces the browser to recalculate layout information for the entire document. But transforms are calculated after the layout has been calculated. They affect where the elements appear on screen, but not their actual dimensions. Yes, it’s weird to think about document layout and rendering as separate concepts, but in terms of browsers, they are.

The latest version of the CSS Transforms specification adds translate, rotate, and scale properties to CSS. Transform properties work much like their corresponding transform functions, but values are space-separated instead of comma-separated. We could, for example, express transform: rotate3d(1, 1, 1, 45deg) using the rotate property: rotate: 1 1 1 45deg. Similarly, translate: 15% 10% 300px is visually the same as transform: translate3d(15%, 10%, 300px) and scale: 1.5 1.5 3 is the same as transform: scale3d(1.5, 1.5, 3). With these properties we can manage rotation, translation or scale transformations separately from other transformations.

At the time of writing, browser support for transform properties is still pretty sparse. Chrome and Samsung Internet support them out of the box. In Firefox versions 60 and later, support is hidden behind a flag; visit about: config and set layout.css.individual-transform.enabled to true.

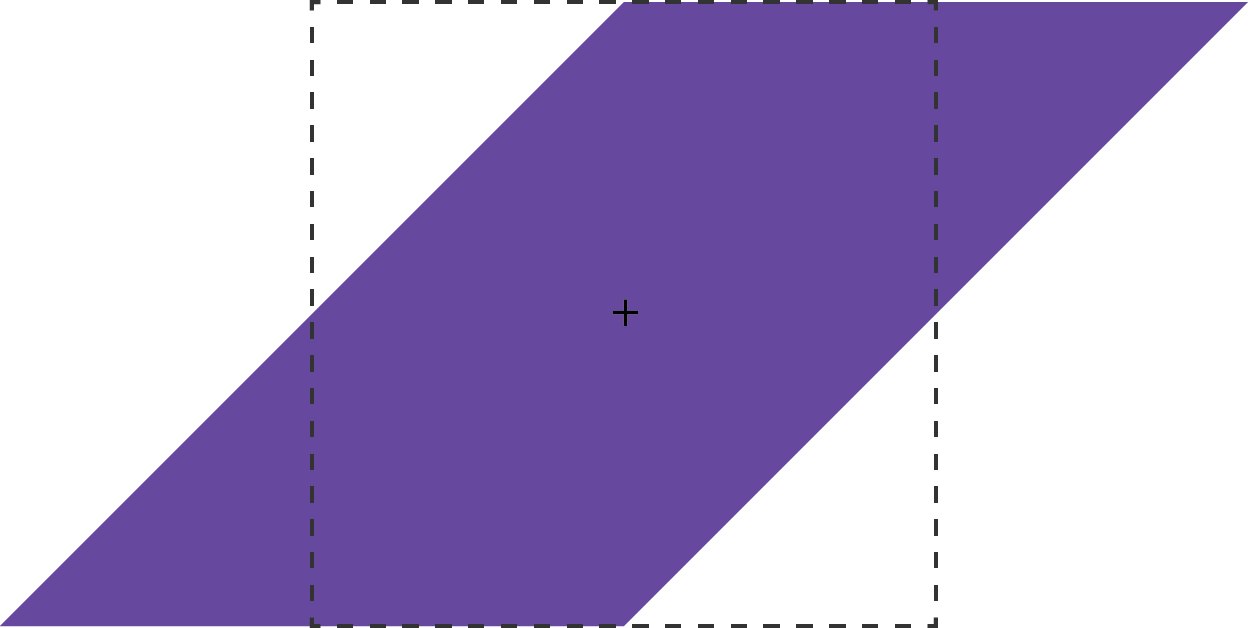

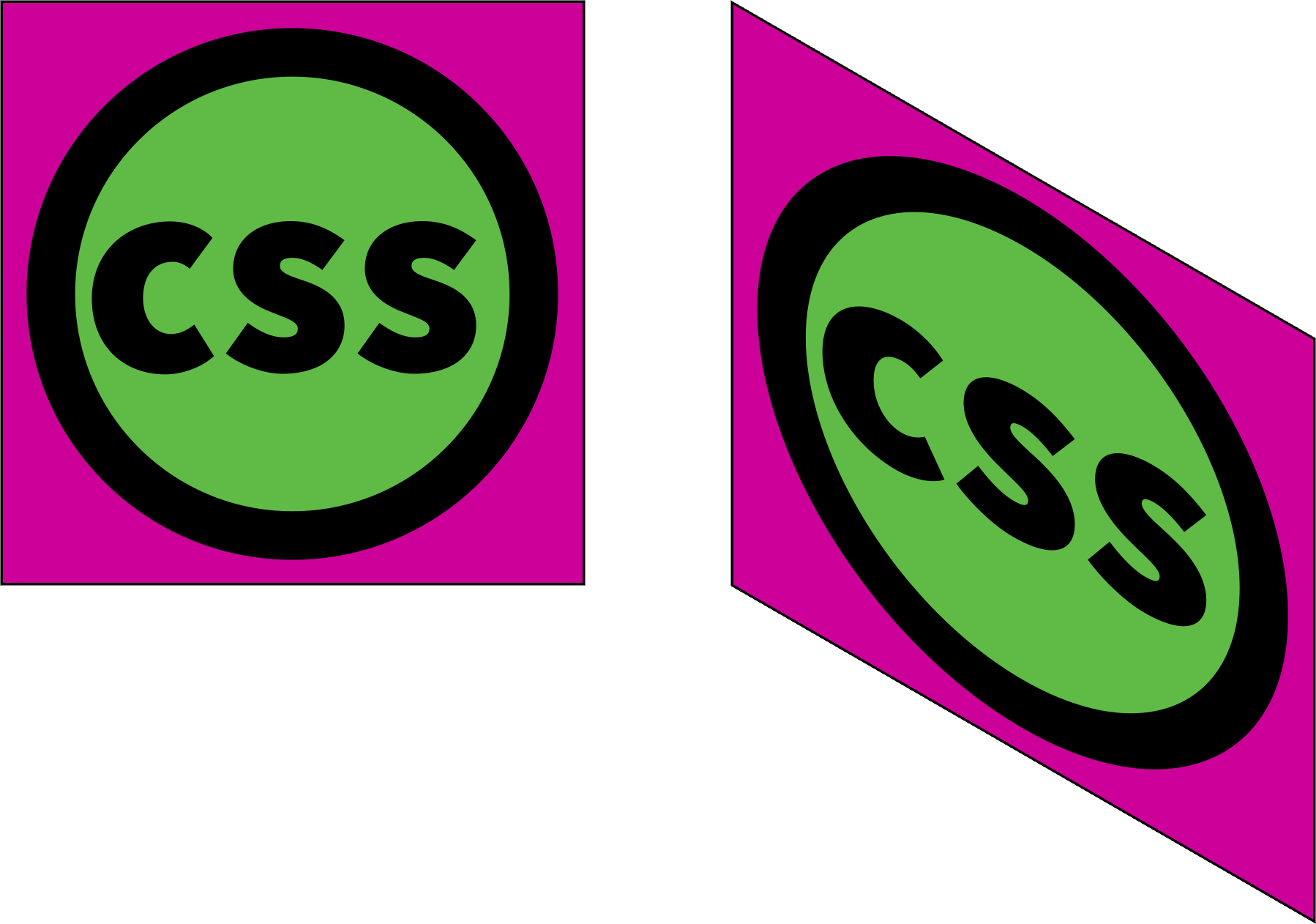

skew, skewX, and skewYSkew transformations shift the angles and distances between points while keeping them in the same plane. Skew transformations are also known as shear transformations, and they distort the shapes of elements, as seen below, where the dashed line represents the original bounding box of the element.

The skew functions—skew, skewX, and skewY—accept most angle units as arguments. Degrees, gradians, and radians are valid angle units for the skew functions, while turn units, perhaps obviously, are not.

The skewX function shears an element in the X or horizontal direction (see teh image below). It accepts a single parameter, which again must be an angle unit. Positive values shift the element to the left, and negative values shift it towards the right.

Similarly, skewY shears an element in the Y or vertical direction. The image below shows the effect of transform: skewY(30deg). Points to the right of the origin are shifted downward with positive values. Negative values shift these points upward.

This brings us to the skew function. The skew function requires one argument, but accepts up to two. The first argument skews an element in the X direction, and the second skews it in the Y direction. If only one argument is provided, the second value is assumed to be zero, making it the equivalent of skewing in the X direction alone. In other words, skew(45deg) renders the same as skewX(45deg).

The post How to Use 2D Transformation Functions in CSS appeared first on SitePoint.

The following is a short extract from Tiffany's upcoming book, CSS Master, 2nd Edition, which will be available shortly.

Think of CSS animation as the more sophisticated sister to CSS transitions. Animations differ from transforms in a few key ways:

The latest versions of all major browsers support CSS animations. Firefox versions 15 and earlier require a -moz- prefix; later version don’t. Internet Explorer versions 10 and 11 also support animations without a prefix, as do all versions of Microsoft Edge.

We can check for CSS animations support in a few ways. The first is by testing for the presence of CSSKeyframeRule as a method of the window object:

const hasAnimations = 'CSSKeyframeRule' in window;

If the browser supports the @supports rule and CSS.supports() API, we can use that instead:

const hasAnimations = CSS.supports('animation-duration: 2s');

As with transitions, we can only animate interpolatable values such as color values, lengths, and percentages.

We first have to define an animation using an @keyframes rule. The @keyframes rule has two purposes:

Let’s create an animation named pulse:

@keyframes pulse {

}

Our keyframes will be defined within this block. In animation, a keyframe is a point at which the action changes. With CSS animations specifically, keyframe rules are used to set property values at particular points in the animation cycle. Values that fall between the values in a keyframe rule are interpolated.

At the minimum, an animation requires two keyframes: a from keyframe, which is the starting state for our animation, and a to frame, which is its end state. Within each individual keyframe block, we can define which properties to animate:

@keyframes pulse {

from {

transform: scale(0.5);

opacity: .8;

}

to {

transform: scale(1);

opacity: 1;

}

}

This code will scale our object from half its size to its full size, and change the opacity from 80% to 100%.

The keyframes rule only defines an animation, though. By itself, it doesn’t make elements move. We need to apply it. Let’s also define a pulse class that we can use to add this animation to any element:

.pulse {

animation: pulse 500ms;

}

Here, we’ve used the animation shorthand property to set the animation name and duration. In order for an animation to play, we need the name of an @keyframes rule (in this case, pulse) and a duration. Other properties are optional.

The order of properties for animation is similar to that of transition. The first value that can be parsed becomes the value of animation-duration. The second value becomes the value for animation-delay. Words that aren’t CSS-wide keywords or animation property keyword values are assumed to be @keyframe ruleset names.

As with transition, animation also accepts an animation list. The animation list is a comma-separated list of values. We could, for example, split our pulse animation into two rules—pulse and fade:

@keyframes pulse {

from {

transform: scale(0.5);

}

to {

transform: scale(1);

}

}

@keyframes fade {

from {

opacity: .5;

}

to {

opacity: 1;

}

}

Then we could combine them as part of a single animation:

.pulse-and-fade {

animation: pulse 500ms, fade 500ms;

}

Though using the animation property is shorter, sometimes longhand properties are clearer. Longhand animation properties are listed below:

| Property | Description | Initial value |

|---|---|---|

animation-delay |

How long to wait before executing the animation | 0s (executes immediately) |

animation-duration |

How long the cycle of an animation should last | 0s (no animation occurs) |

animation-name |

The name of an @keyframes rule |

none |

animation-timing-function |

How to calculate the values between the start and end states | ease |

animation-iteration-count |

How many times to repeat the animation | 1 |

animation-direction |

Whether or not the animation should ever play in reverse | normal (no reverse) |

animation-play-state |

Whether the animation is running or paused | running |

animation-fill-mode |

Specifies what property values are applied when the animation isn’t running | none |

The animation-delay and animation-duration properties function like transition-delay and transition-duration. Both accept time units as a value, either in seconds (s) or milliseconds (ms). Negative time values are valid for animation-delay, but not animation-duration.

Let’s rewrite our .pulse ruleset using longhand properties. Doing so gives us the following:

.pulse {

animation-name: pulse;

animation-duration: 500ms;

}

The animation-name property is fairly straightforward. Its value can be either none or the name of the @keyframes rule. Animation names have few restrictions. CSS keywords such as initial, inherit, default, and none are forbidden. Most punctuation characters won’t work, while letters, underscores, digits, and emojis (and other Unicode) characters usually will. For clarity and maintainability, it’s a good idea to give your animations descriptive names, and avoid using CSS properties or emojis as names.

animation-iteration-count PropertyIf you’re following along with your own code, you’ll notice that this animation only happens once. We want our animation to repeat. For that, we’ll need the animation-iteration-count property.

The animation-iteration-count property accepts most numeric values. Whole numbers and decimal numbers are valid values. With decimal numbers, however, the animation will stop partway through the last animation cycle, ending in the to state. Negative animation-iteration-count values are treated the same as 1.

To make an animation run indefinitely, use the infinite keyword. The animation will play an infinite number of times. Of course, infinite really means until the document is unloaded, the browser window closes, the animation styles are removed, or the device shuts down. Let’s make our animation infinite:

.pulse {

animation-name: pulse;

animation-duration: 500ms;

animation-iteration-count: infinite;

}

Or, using the animation shorthand property:

.pulse {

animation: pulse 500ms infinite;

}

animation-direction PropertyThere’s still a problem with our animation, however. It doesn’t so much pulse as repeat our scaling-up animation. What we want is for this element to scale up and down. Enter the animation-direction property.

The post How to Get Started with CSS Animation appeared first on SitePoint.