This Deep Dive into Cryptography was originally published at Bruno’s Bitfalls website, and is reproduced here with permission.

The media is jam-packed with content about cryptocurrency and everyone is raving about the importance of public and private keys. You’ve heard of encryption, but do you know what it actually is and how it works?

This post will take you back to the basics and explain encryption, describe the different types, and demonstrate algorithm examples, all in a newbie-friendly way. If you’ve ever wanted to understand this but it seemed too complicated, you’ll love this post.

Cryptography

Cryptography is, in a nutshell, turning a message into such a format that it makes sense only to the recipient, and not anyone who might get their hands on it in between.

What is the problem we’re trying to solve?

Suppose there are two people who want to exchange encrypted messages, regardless of the communication channel they’re using — letters, SMS, email … They first have to come to an agreement about a set of rules to apply when encrypting or decrypting the message. These rules are a set of one or more functions which must have a counterfunction. That is, if a given function is used to encrypt a message, then there must exist a counterfunction to decrypt it. In mathematical parlance, such a function is bijective.

The sender of the message applies a function to a set of information and gets an encrypted version of this information which can then be sent to the recipient. The recipient applies the counterfunction to extract the true information out of the encrypted version of the message. If someone in the middle intercepts this communication but they don’t have the counterfunction with which to decrypt the message, they’ll be unable to read it.

Alice and Bob

Let’s make this clearer with the help of a trivial example. Suppose Bob wants to send an SMS containing “I LOVE YOU” to Alice, but can’t risk it being seen by someone else. (Someone picking Alice’s phone up would see the message.) To successfully exchange encrypted messages, Alice and Bob need to come to an agreement about the way of encrypting/decrypting messages. Let’s assume this is the agreement:

Every letter in the message will be replaced with the double-digit index number of that latter in the English alphabet. “A” will be “01”, “B” will be “02”, etc. “00” will indicate a space character. This is their encrypt/decrypt function, and it’s bijective.

| code: symbol | code: symbol | code: symbol |

|---|---|---|

| 00: space | 09: I | 18: R |

| 01: A | 10: J | 19: S |

| 02: B | 11: K | 20: T |

| 03: C | 12: L | 21: U |

| 04: D | 13: M | 22: V |

| 05: E | 14: N | 23: W |

| 06: F | 15: O | 24: X |

| 07: G | 16: P | 25: Y |

| 08: H | 17: Q | 26: Z |

Bob will therefore be sending the message:

09001215220500251521

Should someone intercept this message, it won’t make much sense to them. Their love will remain a secret. Alice, on the other hand, will be able to easily decrypt it and blush.

Symmetric Encryption (with a Private Key)

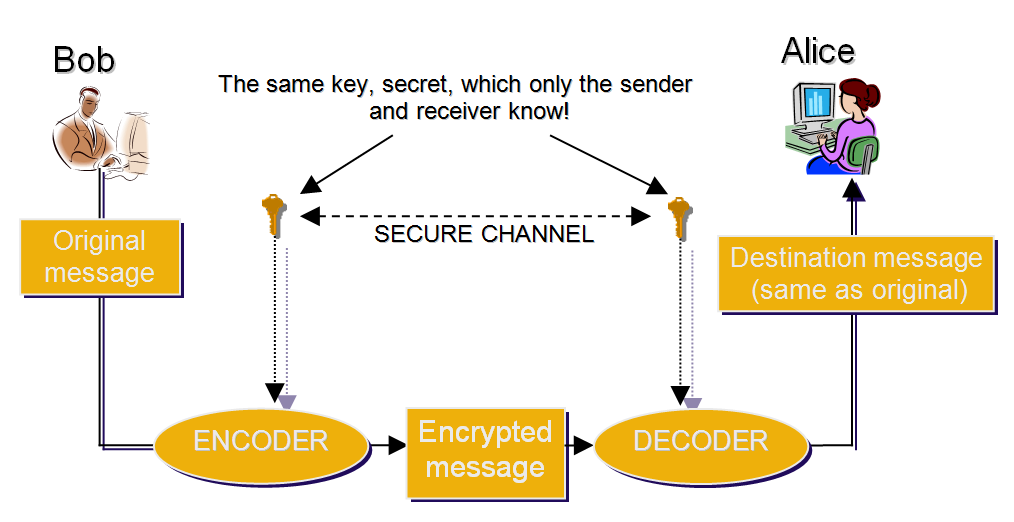

The above outlined approach is called symmetric private key encryption. “Symmetric” indicates that the message can be encrypted and decrypted using the same key (secret). The key (secret) is actually the letter-to-number-to-letter replacement function we described. It looks a little like this:

A system like this might seem perfect at first glance. Of course, a more complex bijective function is required to make this communication truly secure. The system as such is perfectly safe for as long as Alice and Bob can meet and arrange a method of encryption/decryption beforehand. But what if, like in most cases today, the people communicating aren’t actually in close physical proximity, or maybe don’t even know each other? How can they safely exchange a secret key without risk of it falling into the wrong hands?

This is the biggest downside of such a shared key encryption: there has to be a pre-established secure channel via which to exchange the key.

A Possible Solution

It’s clear that, unless a secure channel already exists, it’s nearly impossible to safely exchange the private key. If the channel did exist already, then there’s no need for another one.

The solution is not to find a safe way of exchanging the key, but to eliminate the need for such an exchange altogether. This can be accomplished by adding another key into the mix. One of them would be used only for encrypting, the other for decrypting.

The encrypting key could be available to everyone. In fact, it must be available to everyone, because without it it’s impossible to encrypt messages and send them to the recipient. This key is called the public key.

The other key is used only for decrypting and shouldn’t be sent to anyone. Only the recipient of encrypted information has it, and we call this one the private key.

Asymmetric Encryption (with a Public Key)

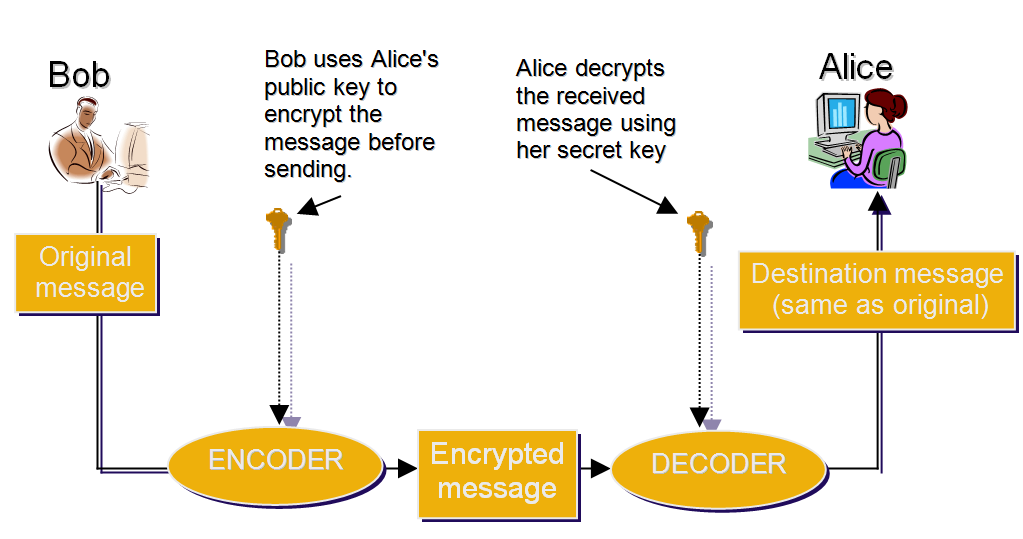

Looking at the image above, we can see that there’s no need for a secure channel to exchange keys through. The asymmetry is in the fact that it’s impossible to encrypt and decrypt the message with the same key. A separate one is needed for each action.

If Bob wants to send Alice an encrypted message, he has to have her public key. This public key could be given to him directly by Alice, or she could just publish it on her website where anyone who wants to send her an encrypted message can find it. When Alice receives the message encrypted with her public key, she uses the private key to decrypt it, which makes the message readable again.

If Alice wants to send a reply, she now needs Bob’s public key. The procedure is identical: she encrypts the message, sends it, and only Bob can decrypt it with his private key.

It’s important to note that to make this kind of communication feasible, the keys need to be generated with procedures complex enough to offset any computer’s ability to guess them for an unreasonable amount of time.

Continue reading %A Deep Dive into Cryptography%

by Bruno Skvorc via SitePoint

No comments:

Post a Comment